Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm: A Prison without Walls, Almost

A lot of us have been in our homes for quite some time now due to the Covid-19 pandemic. For some, they say it is like na-bartolina or imprisoned at a dungeon (some had it worse in derelict quarantine facilities), or a feeling of house arrest especially during the Enhanced Community Quarantine days of Summer. In Palawan, there is a penal colony that is known throughout the country as “a prison without walls” or “where prisoners roam freely.” It is in every tourist itinerary whenever visiting Puerto Princesa—the Iwahig Penal Colony, or officially Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm, as what Bureau of Corrections call it.

The Penal Farm is located 20 kilometers away from downtown Puerto Princesa, passing through Palawan Cherrie trees, fire trees, and acacia trees along the way. That is 45-minute drive or commute in one of the country’s most relaxing sceneries. It is recognized as one of the largest open prisons in the world, with an area of around 34,000 hectares, and is a declared National Historical Landmark of the country in 2004. (National Historical Institute, 2004).

The Beginnings of a Far Away Prison Camp

Even during the Spanish colonial times, there was impression that being sent to Palawan from Manila is already considered an exile or banishment from a very far-away land, known for many for being infested by malaria back then. In fact, some of the first colonizers that were sent here died of this dreaded disease. (Alejandria, 2005).

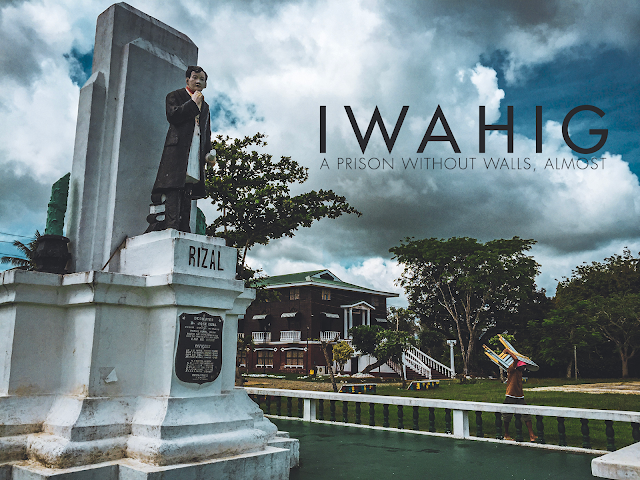

|

| The Iwahig Monument and the Gusaling Pampamahalaan Iwahig Centro |

The American colonial government saw this as a perfect place for a correctional facility to be established, and in 1904 Governor-General Luke Edward Wright authorized the establishment of the penal colony in Iwahig. (Philippine Bureau of Corrections, 2012). Originally, it was supposed to be an alternative prison for those who cannot be accommodated with the overcrowded Bilibid Prison (referring to now Manila City Jail, not yet the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa). It was in 1906 when George Wolfe, which would eventually become its first prison superintendent, visited the site and have it recommended to the Insular Government for expansion. In 1907, the Insular Government has classified it as a penal institution through Act. No, 1723. (Philippine Commission, 1907, pp. 659-660)

|

| The Administration Building. It was built during the 1920s. |

Quoting Rufino Bondad, Technical Assistant Superintendent who wrote the brief history of Ihawig, Maria Carinnes Alejandria mentioned in her paper that the benefits of establishing this far-flung prison facility in Palawan were:

- The relieving of congestion in Bilibid Prison;

- The reward to prisoners for good conduct and industry at Bilibid Prison;

- Retreat for the cure of sentenced prisoners suffering from tuberculosis;

- Relieving society of indigent families (those coming to live with the colonists), without increased expense to the government. (Alejandria, 2005, p. 2)

It was a witness to World War II wherein the Prison Superintendent, Pedro Paje, played a role as a “double-agent” wherein he communicated with the guerilla forces and keeping in close contact with the exiled Philippine government, while keeping his cover as a Japanese collaborator. (Moore, 2016, pp. 86, 135, 208–09, 218–19)

|

| These are some of the warden's quarters in Iwahig. |

1918 Flu Pandemic Reaches Iwahig

For its first few years, it was said to have been beset with escapees and diseases. Interestingly and despite its distance, the 1918 Flu Pandemic that swept the world reached Iwahig. Prof. Francis Gealogo mentioned that it was the only disease that was registered in the prison colony at that year, sickening not only the prisoners but wardens and nurses as well.

|

| A view of the Palawan mountains with its lush tropical rain forests. |

“The disease manifested itself starting on 22 November 1918 spreading to all inhabitants of the colony, including the nurses and servants. Without counting the employees and their families, only five of the colonists remained well. They were given medical assistance in their own houses by the medical personnel of the colony, similar to those who were not gravely ill because of the epidemic. (Gealogo, 2009, p. 285)”

|

| The Iwahig Penal Colony Historic Marker and Monument |

He added that the cluster in Iwahig was traced in an outbreak at Puerto Princesa earlier that November and despite being beset with health problems, the prison colony only had 4% mortality rate. (Gealogo, 2009, p. 285)

A First Timer’s Experience

Together with a friend of mine from Palawan Heritage Center, we went to Iwahig, and for me it was my first time. The land was wide, and the fields are as far as the eye can see. Different farm animals such as cows, carabaos, and ducks were raised just before we enter the colony proper. The mountains at the background were thickly covered by green canopy, still giving that virgin forest feels. It was hot and humid at that time, as the southwest monsoon or habagat has given us time for some sun that morning.

|

| Believe it or not, this is already part of the Iwahig Prison and Penal Colony. Farm animals are raised by inmates. |

While there are facilities that have fences like the Maximum and the Medium Security prisons, the rest of the camp was noticeably—no fence or walls at all! In fact, it feels it is more open to the public than the gated subdivisions and villages that we have in Greater Manila.

I was not sure whether I am interacting with the warden, the family, the prisoners, but the community feels like some far-away barrio in the province.

Iwahig Central: Seemingly a Town of its Own

When we reached the Central colony, we were greeted by a large plaza. While Iwahig was an institution built during the American colonial era, the setup of the central plaza was similar to that of a central plaza in a pueblo or a reduccion. The most important institutions in the community are all located surrounding the plaza, with some adjustments.

|

| Iwahig's main plaza. Well-trimmed and clean. |

Right at the southeast part of the plaza was a seemingly art-deco monument of Jose Rizal. It was inaugurated on Rizal Day, 1938 after almost two years of construction. Somehow its presence brought a semblance that this penal colony looks like a far-away Philippine town.

|

| Rizal Monument (inaugugrated 1938) and the Recreation Hall behind. |

To the northwest, is the Administration Building believed to have been built in 1922 and Gusaling Pampamahalaan ng Central Sub-Colony. These serve as the government offices of the community. Their architecture is reminiscent that of the Filipino bahay-na-bato and Gabaldon School Building respectively, with raised floors and high ceilings adopted to the tropical climate Palawan has.

|

| The Administration Building looks like your typical Presidencia or Municipal Hall during the American Colonial Era. |

To the Northeast is the Saint Joseph the Worker Church that serves the Catholic populace of the place. Though unlike the Philippine Hispanic plazas, the church itself does not dominate the plaza complex. That is reserved with another heritage building.

|

| The newly-renovated Recreation Hall of Iwahig Prison and Penal Colony. |

|

| The cavernous Recreation Hall of Iwahig. |

To the southwest of the plaza is the big wooden Recreation Hall, built in 1924. It is the largest wooden structure I have seen so far in Palawan, and at that time in 2019, was just rehabilitated by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines with initial amount of PhP200 million in 2016. (National Historical Commission of the Philippines, 2017). Inside was a multi-purpose hall, fit enough for one or two badminton courts (the warden, who was on break, had his badminton at that time when I went here). There were several household settlers who were cleaning up the massive hall. It was airy and it does not feel stuffy. One of the house-help, who was a prisoner, was able to tour me around the massive hall. It has a theater and down at the ground floor will be a planned museum. After our tour, he let me go to the souvenir shop where items made by prisoners themselves were sold to tourists.

|

| The big doors, windows, and high ceiling brings natural ventilation--something that architects may have to look post-Pandemic. |

Life Inside the Prison without Walls

I remember the house-help inmate telling how it was living here, and he said that they have rations, they also earn a little for some noodles. It was way better than being in an ordinary prison, where you can still go around the community without eyes prying on your every movement. They too have their own groups or fraternities inside, yet it functions as a support group.

|

| Some inmates taking a breather underneath a tree in that hot and humid late morning at Iwahig. |

The article of Maria Carinnes Pamintuan Alejandria entitled “Iwahig Penal Colony According to the Inmates’ Perspective: 1904- Present” posted on ResearchGate gave us a glimpse of the life, the structure, and the community of the inmates based on the perspective of the prisoners themselves. It gave us how food was rationed and how life is inside such as the prisoners’ preference of being in a malaria-infested community than the guardhouse that reeks of “Bilibid Muntinlupa.” (Alejandria, 2005, p. 4)

I had only a short time visiting the Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm, but somehow it was enough for me to know the Diwa of the place—a penal colony, a tourist spot, and a spot of hope and atonement. As I head back to Puerto Princesa that June late morning, I realized that with compassion and social justice can go a long way in making life of folks better.

References

Alejandria, M. P. (2005, January). Iwahig Penal Colony According to the Inmates’ Perspective: 1904- Present. Retrieved from ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319953702_Iwahig_Penal_Colony_According_to_the_Inmates%27_Perspective_1904-_Present

Gealogo, F. A. (2009). The Philippines in the World of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Philippine Studies 57, No. 2, 261-292.

Moore, S. (2016). As Good As Dead: The Daring Escape of American POWs From A Japanese Death Camp. New York: Caliber.

National Historical Commission of the Philippines. (2017, May 23). ITB Restoration of Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm Recreation Hall Puerto Princesa City, Palawan. Retrieved from National Historical Commission of the Philippines: https://nhcp.gov.ph/itb-restoration-iwahig-prison-penal-farm-recreation-hall-puerto-princesa-city-palawan/

National Historical Institute. (2004, August 13). Resolution No. 06, S. 2004 – Declaring the Iwahig Penal Prison and Farm a National Historical Landmark. Retrieved from National Historical Commission of the Philippines: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9c6mrxI4zoYVmExMVFET2xvWTA/view

Philippine Bureau of Corrections. (2012). Prison Facilities: Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm. Retrieved from Bureau of Corrections: https://www.bucor.gov.ph/facilities/ippf.html

Philippine Commission. (1907, October 16). Official Gazette. Retrieved from National Library of the Philippines Digital Collection: http://nlpdl.nlp.gov.ph/OG01/1907/oct/16/datejpg1.htm